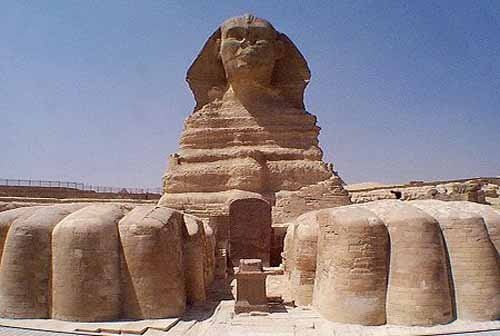

The Great Sphinx of Giza is an awe-inspiring monument from ancient Mısır, standing guard near the iconic pyramids. This colossal limestone statue, measuring 240 feet long and 66 feet high, depicts a lion’s body with a human head adorned by a royal taç. Carved during the reign of Pharaoh Khafre around 2500 BCE, the Great Sphinx remains shrouded in mystery, especially regarding its missing nose.

This article delves into the fascinating theories and scientific research surrounding the missing nose of the Great Sphinx. It explores the construction and characteristics of this ancient wonder, examines popular hypotheses about the nose’s disappearance, and uncovers modern discoveries that shed light on this enduring enigma.

The Great Sphinx is an awe-inspiring monument carved from a single piece of limestone, measuring approximately 240 feet (73 meters) long and 66 feet (20 meters) high. It features the body of a lion and a human head adorned with a royal headdress, believed to represent the pharaoh Khafre. Pigment residue suggests that the entire statue was once painted, adding to its grandeur.

The construction of the Great Sphinx is a remarkable feat of ancient engineering. According to estimates, it would have taken about three years for 100 workers, using stone hammers and copper chisels, to complete the statue. One of its most distinguishing features is the lack of a nose, which was likely lost due to erosion or intentional damage over time.

The Sphinx’s disproportionately large head has led some researchers to theorize that it may have been recarved multiple times by different pharaohs to align with changing aesthetic preferences. Some even speculate that the original head might have depicted a ram or a hawk, suggesting the Sphinx could be older than initially thought.

The Great Sphinx holds significant symbolic meaning in ancient Egyptian culture. Its mixed form, combining a lion’s body with a human head, is believed to represent the pharaoh’s dual nature – the link between mankind and the divine. This shape-shifting symbolism is thought to be appropriate for the king, who stood at the threshold of these two worlds.

The Sphinx’s association with the sun god Atum and its alignment with the solar cycle further reinforce its connection to solar worship and the royal sun cult. Its position at the entrance to the Giza necropolis also suggests it served as a guardian, warning against evil forces.

Overall, the Great Sphinx is a testament to the ingenuity and cultural significance of ancient Egyptian civilization, captivating the imagination of people worldwide with its grandeur and enduring mysteries.

One of the most enduring legends surrounding the Great Sphinx’s missing nose is the theory that it was damaged by cannon fire from Napoleon’s soldiers during the French military campaign in Egypt in 1798. This myth, however, has been widely debunked by historical evidence.

Sketches of the Sphinx by Danish artist Frederic Louis Norden, created in 1737 and published in 1755, clearly depict the monument without a nose, predating Napoleon’s arrival in Egypt by several decades. Furthermore, accounts from Napoleon’s expedition do not mention any intentional damage to the Sphinx’s nose caused by his troops.

A more plausible explanation for the missing nose comes from the 15th-century Egyptian Arab historian al-Maqrīzī. He attributed the disfigurement to a Sufi Muslim named Muhammad Sa’im al-Dahr, who was outraged by the local peasants’ practice of making offerings to the Sphinx in 1378 CE to control the flood cycle and ensure a successful harvest. In an act of religious iconoclasm, Sa’im al-Dahr vandalized the Sphinx’s nose, and he was later executed for his actions.

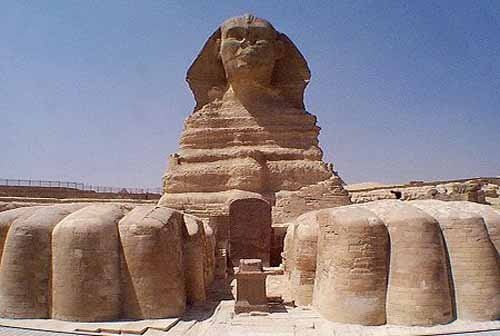

While intentional damage may have played a role, environmental factors such as erosion and weathering over the centuries could also have contributed to the deterioration of the Sphinx’s nose. The limestone structure has been exposed to wind, humidity, and pollution, leading to the gradual erosion of its features.

It is worth noting that the Sphinx’s nose is not the only missing feature. Part of its royal cobra emblem from the headdress and its sacred beard have also been lost over time. These missing elements further underscore the impact of both human actions and natural forces on the preservation of this ancient wonder.

Extensive scientific research has been conducted to unravel the mysteries surrounding the erosion patterns observed on the Great Sphinx and its enclosure. Geologist Robert Schoch argues that the Giza Plateau is “criss-crossed with fractures or joints millions of years old” and that “fissures such as those on the Sphinx enclosure wall can only be produced by water, primarily precipitation.” After investigating the enclosure’s geology, Schoch concluded that the most prominent weathering pattern was caused by prolonged and extensive rainfall, pointing to the well-developed undulating vertical profile on the enclosure walls.

Schoch contends that because the last period of significant rainfall seemingly ended between the late fourth and early 3rd millennium BC, the Sphinx’s construction must date to 5000 BC or earlier. However, this theory has faced criticism from Egyptologist Zahi Hawass, who argues that Schoch “never demonstrates why the rainfall over the last 4,500 years would not be sufficient to round off the corners,” citing the many downpours at Giza over the past decades.

While erosion may have played a role, archaeological evidence suggests that the Sphinx’s nose was intentionally damaged with tools. Upon examination, the Sphinx’s face shows that rods or chisels were hammered into the nose area, which were then used to pry it off. The 1-meter wide nose has still never been found.

Archaeologist Mark Lehner performed an archaeological study on the Sphinx and concluded that its nose was intentionally broken with instruments sometime between the 3rd and 10th centuries AD. Additionally, there are holes in the Sphinx, including at the top of its head, and many New Kingdom stelae depict the Sphinx wearing a crown, leading to theories that these holes could have been anchoring points for such adornments.

Historical accounts provide insight into the potential causes of the Sphinx’s missing nose. The 15th-century Egyptian Arab historian al-Maqrīzī attributed the disfigurement to a Sufi Muslim named Muhammad Sa’im al-Dahr, who was outraged by the local peasants’ practice of making offerings to the Sphinx in 1378 CE to control the flood cycle and ensure a successful harvest. In an act of religious iconoclasm, Sa’im al-Dahr vandalized the Sphinx’s nose, and he was later executed for his actions.

However, sketches of the Sphinx by Danish artist Frederic Louis Norden, created in 1737 and published in 1755, clearly depict the monument without a nose, predating Napoleon’s arrival in Egypt by several decades. This evidence contradicts the popular myth that Napoleon’s soldiers were responsible for damaging the Sphinx’s nose during the French military campaign in Egypt in 1798.

The Great Sphinx of Giza, an iconic symbol of ancient Mısır, continues to captivate and challenge modern-day observers. Despite its enduring grandeur, this monumental statue faces significant conservation challenges, the impact of tourism, and ongoing mysteries that persist to this day.

Over the past few decades, the Sphinx has visibly suffered from increased erosion and deterioration of its outermost surface layer. The combination of wind, humidity, and air pollution from nearby urban areas has taken a toll on the limestone structure. Salt and gypsum crystallization, mobilized by groundwater percolation and moisture from the air, have caused the outermost layers to flake off, exposing the Sphinx to further damage.

The Sphinx’s location on the Giza Plateau, near the fertile banks of the Nile River, has made it vulnerable to the effects of both desert and agricultural environments. Decades of overtourism have also contributed to irreparable damage, with overcrowding, erosion from footsteps, and even vandalism and theft straining the towering structure.

Despite these challenges, the Sphinx remains a cultural icon and a testament to the ingenuity of ancient Mısır civilization. Ongoing efforts by Egyptian authorities and international organizations aim to preserve this wonder for future generations while managing the impact of tourism and urban development.

Even as conservation efforts continue, the Sphinx retains its air of mystery. The true origins and purpose of this colossal monument remain subjects of debate and speculation. Questions surrounding the original appearance of its head, the potential existence of a sacred beard or crown, and the reasons behind its missing nose continue to intrigue scholars and visitors alike.

As modern technology and scientific analysis advance, researchers hope to unravel more secrets about the Sphinx’s construction, symbolism, and the civilization that created it. However, the enduring allure of this ancient wonder lies in its ability to captivate the human imagination, inspiring awe and curiosity across generations.

The Great Sphinx of Giza stands as an enduring symbol of ancient Egypt’s ingenuity and cultural significance. Despite the missing nose and other signs of erosion, this colossal monument continues to captivate visitors from around the world with its grandeur and enigmatic aura. While theories abound about the causes of its disfigurement, the true origins and purpose of the Sphinx remain shrouded in mystery, inviting ongoing research and exploration.

Ultimately, the Sphinx’s allure lies not only in its physical form but in its ability to transcend time and connect us with the rich heritage of a civilization that left an indelible mark on human history. As efforts to conserve and protect this ancient wonder continue, the Great Sphinx will undoubtedly remain a source of fascination, inspiring awe and sparking the curiosity of generations to come.